Transcript:

Ruth: Hello, this is Ruth with the fourth in our Hague Mothers series of podcasts. The Hague Mothers’ project is intended to raise awareness about the impact of The Hague Convention legislation on mothers and on their children.

Over 100 countries have signed up to the Convention, including the UK, the USA and Australia. The latter is known for its particularly narrow interpretation of the law and its disinclination to consider the circumstances which might lead to a mother fleeing across international borders with her children. But to be fair, it’s not alone in this.

To find out more about the Australian context, I’m absolutely delighted to be talking with Gina Hope Masterton who is working with us on The Hague Mothers’ project. Welcome Gina.

Gina: Hi Ruth. And thank you for inviting me to be a part of this podcast.

Ruth: An absolute pleasure. So a little bit about Gina.

She trained as a barrister. She’s currently a post-doctoral researcher at the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane. Her research involves looking at transportation justice for indigenous women in Australia who are domestic violence victims, and identifying obstacles to justice.

Both Gina’s Masters and her PhD were focused on The Hague Convention and its effects on women and children. And she is absolutely passionate about righting the wrongs of this legislation. In a recent email to me, she wrote:

‘No law, which abuses women and children should be left unchallenged. I will do whatever is in my power to get this Convention amended. It should have happened decades ago.’

We agree Gina. And if this wasn’t a podcast, you’d see me punching the air! Could you tell us how you came to be interested in The Hague? What drives you?

Gina: In 2013, my own sister, Rebecca was ‘Hagued’ – that’s what I call it when women go through the Hague legal process and come out the other end like they’d been in is a washing machine and, you know, they’re left kind of wondering what happened.

So she was Hagued by the Australian family court actually. She’d been married to an American citizen for a couple of years and had a child. However, after secretly suffering years of domestic violence perpetrated by her child’s father, she fled back to Australia – which is her home country – with her infant child.

Her husband then used the Convention against her and filed a Hague return application with the Australian government. And without knowing anything about him or the circumstances around why my sister fled, the Australian family court ordered her to return her child to the USA – in effect to her abusive husband. I’d been a lawyer for about 13 years at that time. And I’d never even heard of The Hague Convention until my sister got persecuted under this law.

Ruth: I think that’s a common experience. We’ve been talking to lots of people – to lawyers, to academics, to domestic violence professionals, to Hague mothers, themselves – and very few of them have ever heard of the Convention until they’re caught up in it. As you said, it’s like being put through a washing machine and wrung out and you come out the other end thinking: what just happened?

I know we’re going to hear from your sister, Rebecca, in a future podcast because you’re going to interview her for this Hague Mothers’ project. So, this is personal as well as professional.

Gina: It is. When I found out just how far the tentacles of this Convention reach and the absolute devastation it can wreck on women, and their children, I will continue to work to make it a better law for women.

Ruth: I’ve suggested that Australian courts are particularly rigid in their approach to the Hague. Do you think this is a fair assessment, Gina?

Gina: Yes, I do. Ever since the Convention came into force in Australia on the 1st of January 1987, it’s been applied strictly in all cases, even in cases where domestic violence is raised. It’s still very strictly applied by the family law courts.

I did my Masters on The Hague Convention itself and its background and the way it operates. And I came across a case from 2008 called Papastavrou and it involved a Greek woman, who was living in Greece with her husband, but I think she had Australian citizenship as well, and he’d been violent to her for several years.

She fled to Australia – where she had family – with her child, her son, he was also autistic. She just had to get away from her husband because the abuse was ongoing, and she went through a Hague case here in Australia.

And it was one of very few cases where I’ve seen the ‘grave risk of harm’ defence exception raised and been successful. It was only because she had suffered such extreme physical abuse, resulting in brain damage where she was having seizures and she had vertigo, that the family court said something along the lines of, they wouldn’t normally allow domestic violence to satisfy the grave risk exception. However, in this case, the woman was so badly affected that they upheld her grave risk of harm exception.

And that’s a very high bar set by the Australian family court that, if you can show you’re brain damaged from physical abuse, then we may consider this grave risk of harm argument that you’re making. I haven’t seen any other case since then, and that was 2008. So it was quite a while ago. It’s not like that set a precedent; evidence of domestic violence has not been allowed to satisfy the grave risk of harm exception.

Ruth: So even that high bar is not being followed through in any way?

Gina: No. I sat in on another case a couple of years ago in Brisbane and the mother was from a South American country and her husband was running a drug cartel. She had clear evidence from the courts there, that he was a violent criminal. She had domestic violence orders against him. He was 10 or 15 years older than her, sort of coercive control and threats, threats to kill her family.

And yet, the Brisbane family court ordered her to return her five-year-old son to that country. And she went with the son and apparently went into hiding and I never heard from her again. I hope that they’ve been safe ever since then.

This is the type of thing. You can come with boxes of evidence of showing that if you return, if your child’s returned, that physical harm could occur and yet the courts will be so reluctant to not make a return order. I was just flabbergasted after that case. I didn’t know what you had to do to be able to have a finding made in your favour.

Ruth: I know that in Australia, as elsewhere, concerns about the injustices perpetrated by The Hague Convention are regularly being raised – obviously by you, but also by other lawyers and academics. And even by Diana Bryant, the former Chief Justice of the Family Court, and indeed The Hague itself. I’m just wondering if any of this has changed anything.

Gina: I respect Diana Bryant a lot. She was the former Chief Justice of the Family Court and she was part of the HCCH committee that looked at this back in 2017 and put out another guide to domestic violence related cases. That was the first time they actually acknowledged this as an issue, as a problem. It’s a growing problem.

But they didn’t take that opportunity to go, look we’re really going to make a change here; we’re going to amend it, or we’re going to tell signatory countries that they should look at their own laws and add some kind of domestic violence defences into their laws so that these cases are handled differently.

They just put out another guide which said to judges ‘do what you think is right’. And that’s not really telling judges that this is an important issue and they really need to look at the facts of domestic violence related Hague cases. So that was a wasted opportunity and I was very disappointed. The only good thing was that the HCCH acknowledged that domestic violence related Hague cases are growing in number. But nothing really changed here.

Ruth: I’m really interested in your approach of going through stories; getting to the real human heart of the matter rather than simply staying at the legal level. Some of those stories I’m sure have been profound in their impact on you. Do you want to give us some examples of women who’ve tried to flee with their children and been sent back?

Gina: Well, what I found with the ten women I interviewed was they all had tried to access help in their countries with the authorities there before any notion of leaving occurred to them. They got domestic violence protection orders; they sought legal advice; they went to doctors and psychologists. They tried to get the help they could through the available resources they had until it came to a point – some of these women were abused for years – and then it came to a point when it really started affecting their children. That was when they realised they had to get out of it some way, they had to put physical distance between themselves and their abusers.

So it was roundabout when their children became school age that there was this pattern where the women would finally decide that they had to physically remove themselves and their children from this toxic environment.

Nine out of the ten women had professional or academic qualifications, they were running businesses or working in professional jobs. They were intelligent and accomplished women who just ended up finding themselves in a situation with their partners becoming abusive and it gradually getting worse over time. They had tried to utilise the system to protect themselves and their children before eventually leaving.

But then when they do leave and they’re in a situation where they’re going through The Hague process, particularly in Australia, I found that the judges here were very harsh. They were very judgemental, they took it very personally. It wasn’t just an administrative type matter, which The Hague is – it’s administrative, it’s civil, it’s not criminal – but the judges here really did treat the women like they were child abductors, that they had done something criminal, and the women felt that way too.

It’s just devastating. They lost everything. They lost their homes, they lost their incomes, they lost their careers, they lost most of their personal affects, they lost relationships, they pretty much lost everything. And some of them even lost contact with their children. Some of them lost their liberty, some were threatened with going to jail if they didn’t cooperate with the authorities.

So there’s a lot on the line when you cross an international border with your child. These decisions are not made lightly. But judges don’t seem to take that into account in Australia. They just look at you as a woman depriving a father of time with their children, which is a very narrow view to take.

Ruth: Yes, it is indeed. So have there been any successes in terms of the women you interviewed actually managing to not return with their children?

Gina: No. They all had to return. [The courts] don’t order the mother to return. They can’t do that. They order the child to be returned and then the mothers go with the children because they want to, they choose to. Once they do they have to then deal with the domestic family court in their jurisdiction, to deal with child custody issues and parenting issues.

In some cases, the fathers have already gone to court and gotten full custody of the child while the mother was in the other country – in her absence they managed to go to court and get orders giving them full custody of the child. So once the mother comes back with the child, the father’s allowed to swoop in and take the child. If the mother doesn’t go to jail that’s a positive, but then she’s left without anything and starting her life over again.

But three of the women that I interviewed got relocation orders – which took a lot of time and a lot of money – allowing them to relocate back to their country with their child, which is what they did in the first place. They had to get returned and then do the relocation application. So it’s a big circle, but three of them got to go back to their home countries with their children.

And what I can say about all of them is, none of them returned to their abusive partner. So that’s a bonus. I was happy for them that they didn’t have to do that. But their lives are forever altered, forever changed and not in a good way. They carry that with them, for the rest of their lives, this whole Hague experience.

Ruth: Absolutely. Yes, it has a profound impact and of course, an impact on the mother has a huge impact on the child, which is the other aspect that The Hague doesn’t seem to take into account, that being parted from your mother, your primary carer, has an impact.

Gina: Absolutely.

Ruth: The more I hear about The Hague, the more I wonder if it’s beyond redemption or if anything can be done to make it a viable piece of legislation, what do you think?

Gina: Well, I think that it works extremely well for the cases that it was designed to deal with, and that is cases involving non-custodial fathers who kidnap their children from their mothers and their homes and take them to other countries. That’s what it was drafted for and I think it works very well for those types of cases.

However, when it’s applied to cases involving abused mothers who are fleeing domestic violence as a last resort with their children, it completely fails. It fails the mothers; it fails the children. It just needs to be amended. It needs to be amended by the HCCH and all it would take is the insertion of a few specific domestic violence related defences added to the Convention.

If it can’t be done there, if it’s too hard, then each signatory country really needs to look at their own Hague law and their own Hague regulations, and add their own domestic violence defences into their own laws because this cannot continue.

When the HCCH in 2017 finally got together and met, it was the 7th meeting of the special commission on the practical operation of The Hague Convention, they acknowledged that domestic violence related cases are a big issue and they’re happening all the time. And yet all that came out of that was yet another book of guidelines. It’s a step in the right direction that they’re acknowledging that this is an issue, however, that’s where it finished. So I think it’s up to each country now to recognise this is a problem and to take steps by amending their own laws to better protect women and children.

Ruth: That’s an interesting approach because the idea of tackling the hundred plus signatories to the Convention all at once is quite an overwhelming idea, but if each country can do something towards this, that might help.

Last question, Gina – and thank you so much for all your input and your expertise and your passion – what do you hope the Hague Mothers’ project might achieve and what made you decide to be part of it?

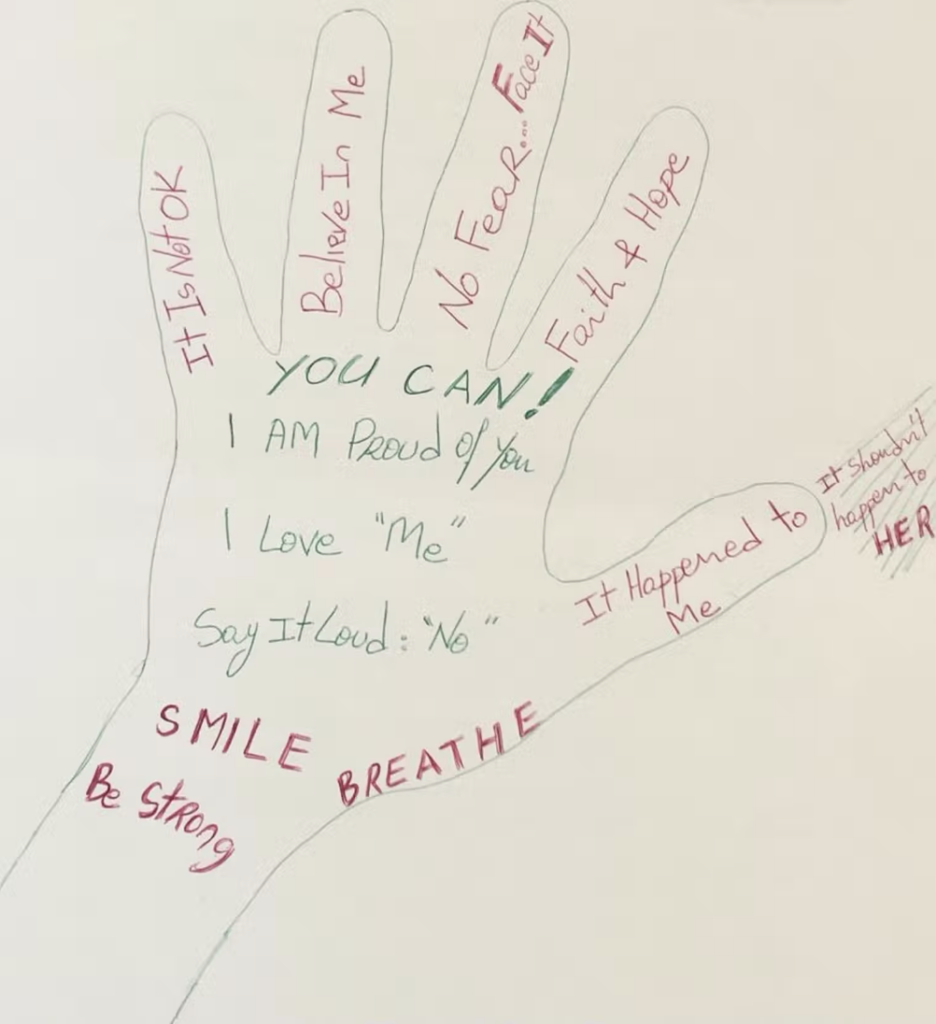

Gina: Well, I am honoured to be a part of this amazing project with all the amazing women who are putting their hands up to try to make change in this area. And I just really hope that our combined voices and experiences will be heard and understood by those who have the power to end the suffering of women and children who are damaged by the Convention.

I want to continue the fight for this change in recognition of my own sister who went through it, the ten mothers I interviewed for my PhD project, and for all the mothers who are getting Hagued every single day around the world. They don’t appear in the media, there’s no statistics kept, they are just another Hague story not everyone will get to know about.

If we have to battle the patriarchy to get this changed, to make life better for abused women and children, then I feel it’s the least I can do. And as a feminist human rights lawyer, I owe a duty to women who find themselves facing this Convention. And I’ll take every opportunity offered to me to work towards getting the changes made.

Ruth: Thank you so much, you are an inspiration you truly are. I actually came across you several years ago when I met a Hague mother and I was reaching out across the world to try and find out who might help. And I reached out to you and you immediately replied with such warmth and compassion, I thought, this is a woman I want to work with. So it’s fabulous to be working on this together with you. Thank you so much, thank you for taking part in this podcast, and thank you for working on The Hague Mothers’ project with us.

We look forward very much to hearing from some of the women whose voices you’ve had helped amplify in our future podcasts. And I hope we hear from you too, as we progress and hopefully make the changes you suggested.

Gina: Thank you Ruth, and I’m happy to do whatever I can to get this all happening.

Ruth: Wonderful. Thank you Gina.

We need to raise awareness about The Hague Convention. Please help us by sharing this podcast and others in the series. If you have experiences or expertise to contribute, please get in touch with us at FiLiA and, if you can, please come to the Hague Mothers’ session at the FiLiA Conference in Cardiff in October. Thank you for listening.