Interview with Anna Kerr of the Feminist Legal Clinic, Australia

There needs to be a presumption in favour of children remaining with their mothers where the mother is the primary care-giver. The onus should not be on a mother to prove that she should retain care of her own child.

Anna Kerr

In this interview, Anna Kerr explains why she believes that the operation of the Hague Convention has become a feminist issue and offers a powerful assessment of the barriers domestic abuse survivors face when trying to break free of their abusers. She also suggests ways in which these barriers might be overcome – an approach which requires significant cultural and social shifts as well as legislative change.

Listen to the interview here:

Anna Kerr is a member of our Australian group and the founder and principal solicitor of the Feminist Legal Clinic in Sydney, a community legal service focused on advancing the human rights of women and children. Anna has been practising as a solicitor for 30 years and now specialises in domestic violence and discrimination law. She also coordinates a Women’s Court Support Service in the Sydney Family Court and is the Australian country contact for the Women’s Declaration International.

Transcript:

Ruth: Hello, I coordinate the International Hague Mother’s campaign. Today I am absolutely delighted to have the opportunity to talk to Anna Kerr a member of our Australian group and the founder and principal solicitor of the Feminist Legal Clinic in Sydney. That’s a community legal service, which is focused on advancing the human rights of women and children.

Anna has been practicing as a solicitor for 30 years and now specializes in domestic violence and discrimination law. She also coordinates a Women’s Court Support Service in Sydney Family Court and is the Australian country contact for the Women’s Declaration International. So welcome Anna, and thank you so much for finding time for this podcast.

Anna: Thank you very much, Ruth. Thanks for that introduction.

Ruth: I wonder if you could tell me a little bit more about yourself. I’ve introduced you briefly, but there’s more to you than that, and also about the Feminist Legal Clinic.

Anna: Yes. Well, like you said, I’ve been a solicitor for over 30 years.

I’ve worked mainly in community legal centres, which are free legal services. So the work I’ve done has always been in the area of social justice. We incorporated Feminist Legal Clinic in 2017. I did that with a group of other women. Unfortunately, it’s continued to be unfunded and it’s entirely operated by volunteers, so it really is a labour of love.

My career began in the Aboriginal Legal Service about 30 years ago I worked in the prison unit there and I worked in both the criminal and civil law sections, and I worked in a string of other community legal centres and government bodies. But my last position before incorporating Feminist Legal Clinic (FLC) was as a supervising solicitor at Women’s Legal Services New South Wales, where a great deal of the work was of course related to family law.

And it was quite obvious to me that there is a shortfall in the justice sector when it comes to meeting the needs of women who are suffering the effects and impact of domestic violence. And the existing community legal centres just couldn’t meet the demand for assistance from women in this area. I think that’s pretty much acknowledged that there is a shortfall in this area, but not much is being done to meet that shortfall.

Our Legal Aid Commission, the majority of their funding goes towards criminal defence work. And of course, that means the recipients of that work are generally men because they are the ones who commit most of the crimes whereas family law is given a smaller slice of the budget, and of course family law is for women, the jurisdiction where they are most involved.

Despite this, the fact that it’s an obvious shortfall FLC hasn’t been able to obtain funding for all sorts of ideological reasons, probably. So we’re unable to make much headway with helping the many women who are desperate for legal representation, in particular in the family court. We do operate an unfunded women’s court support service in the Sydney Family Court this gives a non-legal support to women, so the volunteers, largely women with a social work background.

Our role there is really just wiping away the tears while offering no cure for the pain and suffering these women are experiencing. And so when dealing with women who have had their children forcibly removed from them in circumstances where they fear for the child’s safety, it’s kind of like offering a bandaid for someone who’s just had a limb amputated.

So it’s very difficult I find to have to do something so ineffectual but despite this, the women that we help are extremely grateful, even for that little bit of support that we offer. So we keep trying to do it.

Ruth: Yes, I think The Hague Mothers campaign undergoes very similar concerns in that we have women coming to us in desperate situations and really what we can do to help is minimal.

It’s basically just believing them and supporting the one woman to another. But as you say, even that, even that makes a difference, I think, to people.

Anna: Yeah. Well, we certainly appreciate it.

Ruth: Absolutely. Well, I think people will very much understand how thrilled we were when you joined The Hague Mothers project given all that background and absolute determination to seek justice for women and girls.

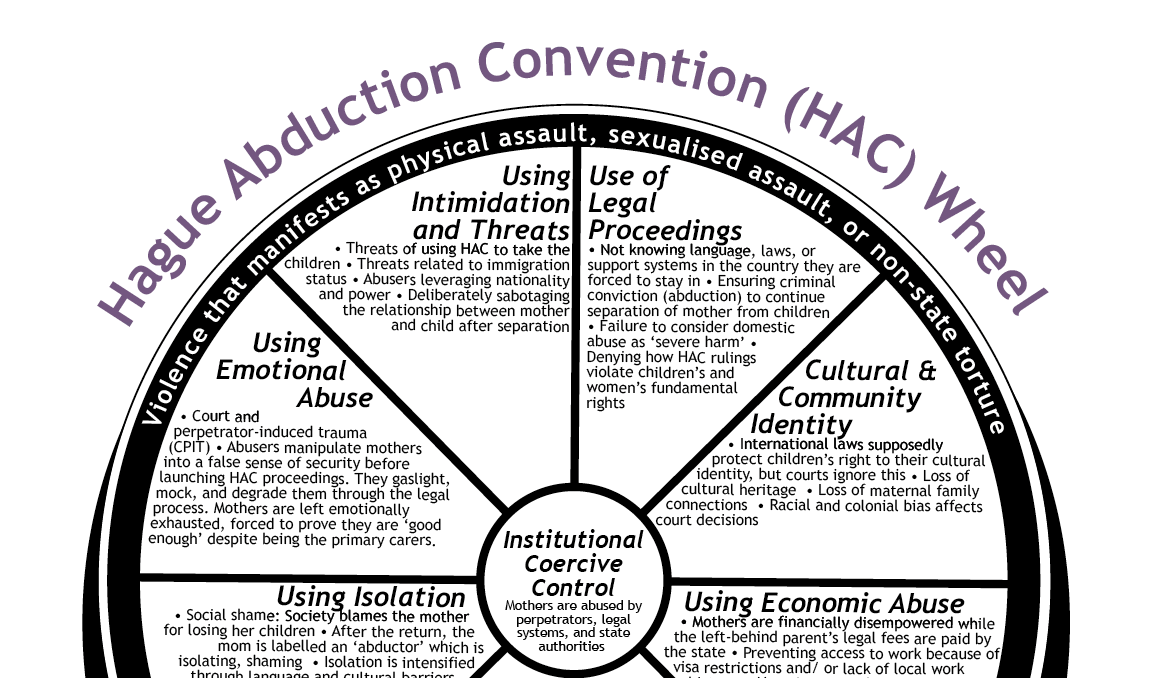

I know in particular from the time we first met that you share our conviction at The Hague Convention is a feminist issue. Would you like to explain why you’ve come to that point of view?

Anna: Yes, definitely. I think for me feminism is about the liberation of women and many women are trapped in abusive relationships, and they’re trapped for many reasons. There’s a number of factors that keep women leaving those relationships. A lot of them are financial, there’s cultural considerations. There’s psychological and emotional ties, but there’s one major factor as well, the legal constraints on women. So specifically family laws that prevent women from making clean break with abusive men, because once they’ve fathered their children, there is no escape and I think very few women realise that, um, that when they conceive a child, they are potentially giving up many human rights, including freedom of movement.

Until that child is grown up, their lives may be ruled by the man who impregnated them, even if it was a rape, sadly, and regardless of the quality of his sub subsequent contributions.

So it’s really something we need to be telling women and girls much earlier so that they really take seriously those relationships because so many women underestimate the extent to which their lives are going to be controlled in this way.

So The Hague Convention on child abduction, is just one of the tools that’s been incorporated into our domestic family laws in Australia as it has been in, in many countries around the world. And it’s just one very powerful tool that prevents women from escaping. So that may be women who are from overseas, who’ve conceived a child with an Australian father, for instance, who become trapped here and unable to return to their families overseas when the relationship breaks down and they find that they can’t leave Australia, they’re stuck.

In other cases, of course, it’s Australian women who are overseas and are unable to return home. So yeah, it’s about a very powerful instrument whereby the state assists men largely to control the lives of women and children.

It’s sad because it was seen as something that was going to help women, but it’s absolutely, it would appear to be just a completely an instrument of patriarchy.

Ruth: And how much appreciation of that reality do you think there is Amongst politicians and amongst the justice system in Australia? Do they know this is happening?

Anna: No, I don’t think many people generally are aware of it until they’ve been involved in the family court. So people then have a heightened awareness of it. They’re oblivious to it. I think that the public generally are oblivious to it and have a perception of the family court and what’s happening, which is completely an alternate reality.

There’s this idea that it’s a jurisdiction where women are getting their way, where women’s interests are favoured, that the mothers have an advantage and in fact, what we are saying is quite the opposite. The narrative that’s put around is a false one.

And unfortunately it’s very hard because we’re not getting any reporting within the family court because there’s a section 121, which makes it very hard to report on these cases without journalists putting themselves in breach of that legislation. And so it’s a very closed off jurisdiction in terms of the general public knowing what’s happening.

Ruth: I think you’re absolutely right and I think it’s a global problem with family courts, everybody I speak to, whatever country, it’s the same problem. And interestingly in the UK there’s just been a transparency project started where people can report from family courts and it will be interesting to see if that starts to make a change.

As you say, we just don’t know what’s happening at the moment.

Anna: That’s good news. I hadn’t heard about that.

Ruth: It’s very good news.

And, and you’ve spoken many times about the inequality of arms, the mother’s facing extradition and indeed mothers in family courts. Would you tell us of your particular experience in this regard and the impact that you feel that inequity has all women’s access to justice generally? That’s quite a big question. We can do it in bits.

Anna: That’s fine. Um, well, look, there is significant inequality because, um, in most cases, uh, the father is being assisted to bring his application to have the child return to him so the parent who’s seeking the return of the child certainly usually has the support of the government, the central authority, it’s often called.

So in the case that I was involved in, it was a father in New Zealand and the New Zealand government brought the application on his behalf, so his legal costs were completely covered.

Meanwhile, the mother who had fled to Australia to escape domestic violence, she had learning disabilities and she was on a disability pension and despite that, she was refused legal aid because they decided there was no merit. In other words, they felt it was a foregone conclusion that she would have to return to New Zealand.

So they didn’t give her any legal aid, and so she was completely left on her own to defend the application. So our service took the matter on because really she had no other recourse. There was no other service that was willing to help. We managed to secure pro bono assistance from the Bar Association.

But you know, we were allocated a very inexperienced barrister, which was not ideal because these are really difficult cases. They’re very challenging and there’s a very poor success rate, which is why the grant of legal aid was refused. So there was significant in inequality in access to justice, and we were unsuccessful defending the matter.

We took an appeal to the full court of the family court, and that was unsuccessful. And then we sought pro bono assistance from a retired appeals court judge, and we then took it to the high court. But it was ultimately refused leave. And so we went all the way and we did get her some further time with her child that way because of course that process was lengthy but ultimately, all our efforts were to no avail. And the little girl was returned to New Zealand. I think she was like five or six years old. She was returned to a father who was quite clearly a serial domestic violence offender. I mean, the whole process was onerous and I don’t know how anyone in my client’s situation could possibly have done it. She just wouldn’t have been able to do any of it. Even the cost of the printing and binding of the appeal books was prohibitively expensive. We had to make special applications to get those costs covered also by the Bar Association. So yeah, huge inequity. And in the end we were unsuccessful and the mother did not return with the child because she was genuinely fearful for her life. And the child, this little child, was returned on her own.

Fortunately, I heard that the welfare authorities in New Zealand stepped in, and I believe the child ended up being placed with the grandmother rather than the father despite all of that, but you know, it was just harrowing really to see that take place.

Ruth: The right word, harrowing.

And as you say, some women are having to go through this representing themselves and entirely alone. It’s just extraordinary.

You mentioned about legal aid being means and merit tested. I don’t think that’s a system we have here in the UK. Could you explain that double barrier?

Anna: Yeah. In New South Wales at least, I mean, each state in Australia probably has a slightly different system, but it’s certainly means tested. And that means really if the woman has any employment at all she’s not likely, even if she’s just got a low paid part-time job, she’s unlikely to qualify for legal aid. The merit test, well, in cases like this, it’s problematic because they look at it and think, well, it’s got very little chance of success and so they don’t give it a, so that’s a self-fulfilling prophecy, of course.

So while legal aid makes those kind of assessments, those cases are not properly defended and so it continues that the success rate is poor when it comes to defending these applications but yes, they do exercise a merit test on cases. So they’ve always got the possibility of saying, no, we don’t think your case has got any merit. It’s not going to have any chance of success, so we will not give you a grant.

Ruth: And as you say, self-fulfilling prophecy. And presumably it also means that, few lawyers are willing to take on these sorts of difficult cases.

Anna: Well, if the client’s got no money to pay you, so there’s no hope of recovering your expenses, you don’t get paid. In some human rights jurisdictions, we’re able to access members of the bar who are interested in doing them. At least Hague convention actually you’ve got a chance of getting barristers who want to cut their teeth doing something which is a bit human rightsy. But the family law jurisdiction, generally very, very difficult to find pro bono assistance. so that’s how the benefit of The Hague Convention is. They’re fewer of them and they’re a little bit, apparently a little bit sexy for the barristers to take on. It’s just something good happen their CV I gather.

So it’s not completely hopeless in that regard, but the family law jurisdiction generally very hard for women to secure representation once they’ve run out of money, which is quickly usually.

Ruth: Yes, it would seem so. And you mentioned earlier when I was asking you about The Hague Convention as a feminist issue, you mentioned the power of the patriarchal legal system. And I’d like to quote from an extraordinary article you wrote in 2018 extraordinary in terms of its power, which we’ve republished on our website. And in that article you said:

“On the current operation of the law, once a woman can seize a child, regardless of the father’s subsequent level of involvement or conduct, she has unwittingly traded her right to liberty of movement and the freedom to choose her own place of residence if she wants to retain custody of her child. The Australian High court reaffirmed that within this patriarchal legal system, resistance is futile”.

When I first read that and I was just taking this project on, I felt right! Do you continue to feel this way or is it possible to hope for something better?

Anna: I absolutely do, that line ‘resistance is futile’ that was the line from the high court. They said that it would be futile. That was the word they used when knocking back our application for leave to appeal. And for me, it sounded like something out of Star Wars, ‘resistance is futile’ that’s exactly how I felt.

I doubt much has changed. I gather the current attorney general has made some amendments to the regulations, which encourage judges to consider domestic violence when determining whether there is a grave risk to the child however, it’s not mandatory. The wording they’ve used is just that the judge ‘may’ consider that. I don’t think that’s in itself going to make enough of a difference.

In practice it is often a factual dispute about the allegations of violence or abuse. So judges can always still refuse to accept the mother’s evidence. And of course that was my experience that they did refuse it. And the case in which I was involved there was, I thought a variety and I felt very strong corroborative evidence. Aside from the mother’s own evidence, which should stand on its own, frankly, but there was also material from two previous female partners of the father who had had no contact with the mother, and lived in quite disparate locations and who reported similar patterns of domestic violence when they were with him, and the judge found that this material, which fell short, there was no actual conviction, there was police statements, there was social media posts, but they hadn’t pursued it all the way, he hadn’t been convicted. So because there was no actual conviction against the father the judge found that the material didn’t have probative value, which I thought was extraordinarily disappointing because it’s very, very difficult for women to establish these things. And we’d managed to subpoena this evidence from another jurisdiction. Really, it was luck that we were even able to locate it.

Because of course we’ve still got no system in place where women can find out about their partner’s histories and know for sure.

But anyhow, I think in most cases you’ll find that the evidence does fall short of convictions. I mean, it’s a rare case where there actually are convictions against the father and even then it’s not a given that that will mean that the mother will be successful with resisting the application.

So it’s only too easy for judges to dismiss the evidence of mothers who say that men have been violent or abusive and it seems that given this scenario that judges have a tendency to instead prefer the narrative that the women are maliciously concocting allegations of violence to secure an advantage. And so, yeah, in this context, I do feel like resistance is futile. I don’t think the addition, the amendments to the regulations are going to be enough because we have got a culture where that’s what’s happening. They’re favouring the father’s rebuttals over the women’s evidence.

Ruth: It makes it even more extraordinary that, in spite of that, you continue to resist.

As you mentioned, the Australian Attorney General has committed publicly to safeguarding victims of domestic violence or facing a Hague petition, and I appreciate what you’re saying about the fact that things haven’t gone far enough by a long way.

If you could actually ask the Attorney General to make one or two key changes to the implementation of The Hague convention in Australia, and he listened, what would you prioritise?

Anna: So the conventions implemented in Australian law through Section 111 B of the Family Law Act and associated regulations. And there’s this section that establishes rebuttable, presumptions in favour of returning a child under the convention. And I think, unfortunately, I think that’s got to change because I think there really needs to be a rebuttable presumption in favour of children remaining with their mothers, where the mother has been the primary caregiver. which is still true in the vast majority of cases. I think this is not a popular thing to be campaigning for, but I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this, said I cannot see how we are going to restore the best interests of children.

I don’t how we’re going to get that back because, the current provisions inherently favour the interests of the parent seeking the return of the child. And this is problematic because now we’re finding these cases, it’s most often the father, it’s most often the case that it’s the mother who’s fleeing because of domestic violence.

The father therefore has his legal costs covered by the authority, whereas the parent defending the application, which is in the majority of cases now, the mother. It does not, in most cases, have her cost met by the state. So that itself, obviously that’s a recipe for injustice that has to change.

So it’s hard to say which one, which key things needs to change first. They all need to change. The provisions also limit the extent to which a child’s own objections are taken into account, it’s sort of got something there, which basically indicates that the child has to make them very, very strongly before they’ll be taken into account.

And I don’t think that’s reasonable because children often do have affectionate feelings for a father, even when he is unfit to parent. Children do care about their parents’ feelings and in other cases, of course we have children who are actually also intimidated out of expressing their feelings. I would suggest that it’s fathers who are in most cases, more intimidating than mothers and that that’s not a reality that’s taken into account by the legislation.

So I think all of these things, I don’t basically agree that fathers should automatically have rights of custody as provided for in the subsection. I think that there needs to be a presumption in favour of mothers.

And fathers who believe that they should have custody should have to mount a persuasive argument that the mother is unfit. I don’t think the onus should be on a mother to prove that she should retain care of her own child. The work of mothering, in terms of gestation, lactation, all that goes with caring for an infant, the burden of which continues to fall on women in almost all cases, is not nothing.

The physiological attachment between a mother and her child is also not nothing. It’s got to be given weight in the law. The attachment to the mother is very fundamental in a young child’s development. And when this relationship is disturbed, it leaves permanent psychological scars.

It’s not an absolute equivalence by any means because the same cannot be said about the relationship with one’s father. I’m not saying that’s not important. Obviously it is an important relationship, but an infant, for instance, especially when we’re talking about the tender years, a new born infant does not search for their father upon being born.

They don’t suffer immediate distress if they’re not immediately placed with their father. However, if an infant or young child is removed from its mother, it will suffer considerably. There’s just no equivalence. And to just ignore that is just ridiculous and is causing a lot of suffering. So certainly the younger years in a child’s life that that has to be given more weight.

It’s a biological reality. It distinguishes males and females and we can’t just keep ignoring it. so because we are seeing it being ignored in the courts, increasingly, biological realities are being ignored. So I think that unfortunately now, we need to have sex-based language, which seems counterintuitive.

I know feminists have fought so hard to try and get fathers to take parental responsibility, and we still want fathers to take parental responsibility, but these cases we’re discussing are cases where the relationship has broken down and he, the mother is not just alleging, in most cases, a mother doesn’t just ‘allege’ abuse and violence for no reason.

My experience is that mothers want to have a continuing relationship with the father of the child because they need that assistance with raising the child even just to give them a break. So I don’t think these women are just alleging this out of pure mean spiritedness, which is kind of what we’re expected to believe.

I think we need to have sex-based language and a presumption in favour of mothers.

Ruth: That would go a long way. But of course it’s not just a legal change, is it? It’s a social, cultural, brain and heart change. And that takes some doing. Well, with you on the team, Anna, I still have hope.

So thank you so much, Anna, for taking time to do this podcast. Thank you especially for being part of Hague Mother’s project. And thank you for all you do every single day to support women and girls in Australia. It’s an absolute privilege to work with you. Thank you so much.

Anna: Thank you, Ruth, for coordinating and making it all happen and let’s hope we get some great results.