Domestic Abuse: how survivors can get through family law court

Rima Hussein and Imane El Hakimi are both senior lecturers at Northumbria University, and domestic violence survivors. Rima is leading a project with the UK Ministry of Justice, support services and survivors, to create vlogs to help women get through the often traumatic court process; Imane is working with her on a related academic paper. We are delighted that they are now part of our Hague Mothers’ project team. Their experience and expertise will be hugely valuable.

We are grateful for their permission to republish this article.

One year on from the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 being enacted, survivors of domestic abuse in England and Wales are still navigating a broken system. Courts are massively under-resourced and face a huge backlog. Survivors often face cancellations, delays and postponements. And the wait for the next court date can be all-consuming.

In court, survivors’ experiences vary hugely, but there are common challenges, from dealing with solicitors and the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service to being scrutinised as a parent and not being heard or believed. What’s more, victims are often brought to court by their abusers, as a kind of punishment for leaving them.

We are currently partnering with the UK Ministry of Justice, support services and survivors to create vlogs, based on the following advice that we hope will help people get through this process. They are grounded in both research and our personal experiences of surviving domestic abuse and dealing with legal proceedings.

Prepare yourself

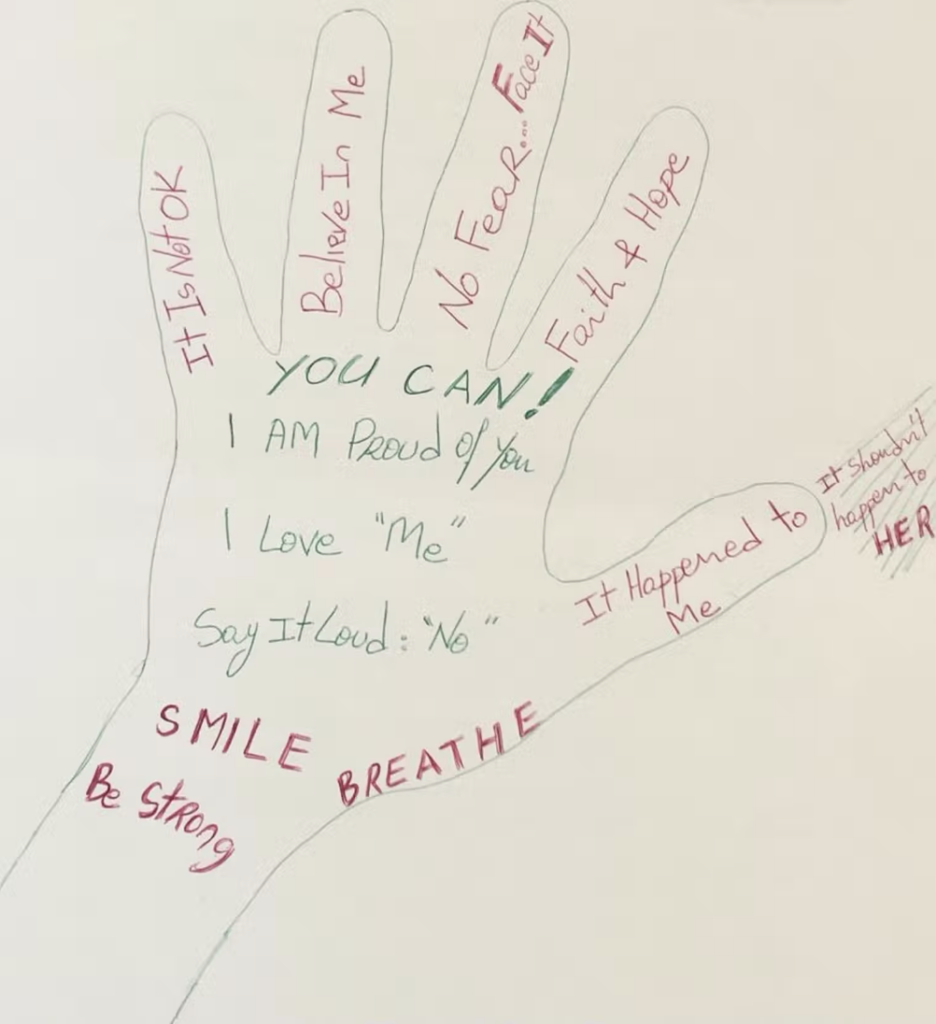

Hearings are hugely taxing. You have to relive traumatic experiences. Prepare yourself for any additional stresses, such as being told that the court didn’t receive your statement. Breathe. There is nothing you can do to change bad organisation but you can control how you react to it.

Make sure you seek advice and support from organisations such as FLOWS, the National Centre for Domestic Violence, CourtNav and support services such as the National Domestic Abuse Helpline, Women’s Aid and Rights of Women.

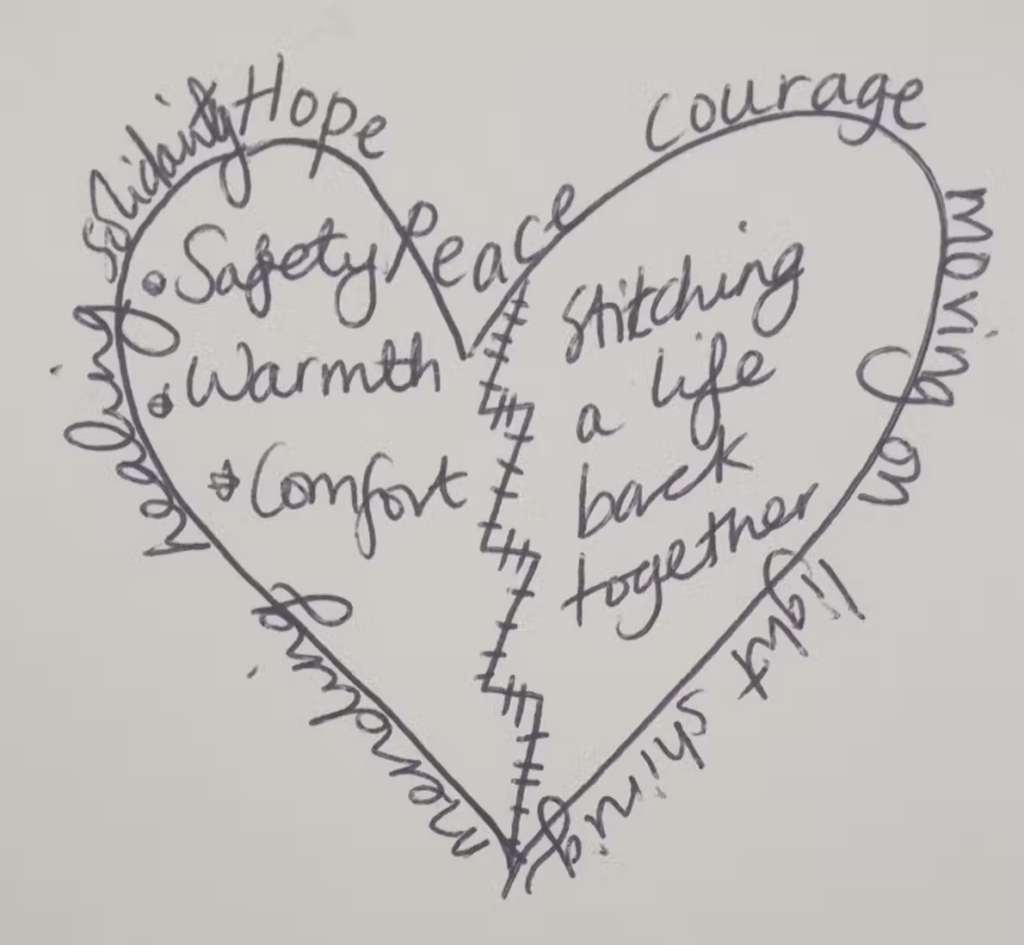

Each hearing needs recovery time. Give yourself space to process what has happened. Draw up a list of the things you love and keep doing them.

Get support in place

Write a list of the people to whom you can turn for support on hard days. Conversely, put in place boundaries with anyone who continues to enable the perpetrator or has a negative effect on you.

In terms of professional support, Claire Waxman, the Victims’ Commissioner to the London Assembly, highlights the importance and benefit of having a single point of contact throughout your justice journey. Local organisations, such as Lighthouse Victim and Witness Care, can put you in contact with an independent domestic violence advisor, an independent sexual violence advisor or an independent violence advocate.

Gather evidence from professionals

Different departments and sections of social services working in a siloed way – independently and without clear communication between them – has been shown to be one of the barriers to effectively supporting domestic abuse survivors in court. So, gather evidence, in writing, from as many professionals (GPs, teachers, social workers) as possible from the start. Log all incidents of abuse with the police. And keep all documentation and communication organised. You will need this in court.

Try to take on board professionals’ proposals when they are helpful and put your child’s welfare first. Challenge the professionals when they don’t do the same.

Know your rights

Research shows that court culture in England and Wales has been characterised by misogyny and victim-blaming. In Ireland, a 2021 report from the Children Living with Domestic and Sexual Violence group submitted to the Department of Justice warned that the child protection services and family court system could sometimes work in opposite directions, endangering victims by being too pro-contact. Childrens’ voices are often unheard too.

Read the government’s welfare checklist, which is used to make decisions about children, and Practice Direction 12J which mandates what should be happening in court to protect domestic abuse victims. If your solicitor is not supporting you or you are struggling to access representation, consider representing yourself to make sure you are heard.

Ask for special measures

You can ask for safety adjustments such as to arrive through a separate court entrance or to leave first after a hearing. You can also ask the court for permission to have the same support worker you’ve had from the beginning (because continuity is beneficial for both you and your child) and for that support worker to be present with you during proceedings.

The process for requesting these measures will differ from court to court, and implementation is patchy. Further, COVID has led a move to remote hearings. Difficulties relating to poor quality video and audio made it more difficult for some litigants to access justice. There is also more pressure on the system, as the rules have changed throughout the pandemic, causing delays and a lack of clarity. All this adds more stress to litigants who have to face their abusers in proceedings or be cross-examined by them. So it is helpful for you to know what the guidance for remote hearings is too.

Know your experiences are valid

We know from personal experience how difficult speaking about abuse is. In June 2022, one of us (Rima) wrote about how long it took me to find the words and courage to be heard: “I am scared to write but know I speak or am lost in the silent void that I have known for too long”.

The acrimonious and hostile experience of a courtroom can make you feel silenced even in a place meant to bring justice.

Going to court has a huge impact on your health and your family. There are no guarantees of a fair outcome and the whole process is dehumanising. What’s more, the end will be an anticlimax. You have been running on adrenaline throughout a process in which there are no winners. There is no easy way through, but each of us finds our own path, and many survivors harness their anger for change. This, after all, is how our project started.